Skills and sustainable job market

This is the first part of a two-part blog; an edited collection of abridged para(s) taken from a working report titled “Employment and Skill: Bridging the gaps for productive India” submitted to the Government of India by ASK-EHS, as part of a policy discussion.

India, uniquely sits at the cross roads of unraveling tremendous economic potential as demonstrated by the GDP figures, each year. And yet, despite its promising economic growth rate, the percentage of worker involved within the informal economy has stayed relatively stable at 92%. The latest unemployment figures (2017-2018) have also hovered around 3.4% (as it currently stands).

Arthur Melvin Okun, an American economist in 1962, proposed an empirical relationship now known as the Okun’s law under macroeconomics: The “gap version” states that for every 1% increase in the unemployment rate, a country’s GDP will be roughly an additional 2% lower than its potential GDP.

In the context of India’s economic scenario – a vast majority under the informal sector and with a relatively recent focus on “manufacturing sector” – the relationship, has been felt by almost all the tiers of employed and unemployed populace.

This blog aims to identify such gaps that directly affect the potential and skill of Indian workforce based mainly within the industrial domain – ranging from unskilled to semi-skilled and skilled workers. And, juxtapose ‘their’ dilemma in the rapidly growing Indian economy and economies around it, which seek migrant workers for mutual benefit. The challenges that do not allow a worker and their skills to remain ‘relevant’ within a short span of say, 5 years, i.e. only if technological advancements, also, follow the similar pattern of growth.

The best-case scenario for any nation state in the modern free market economy is to learn from where the others’ failed, faltered or simply couldn’t forecast – today, global business and policy decisions are more likely to impact Indian workers than say twenty years ago. The relationship based on reciprocation and learning has enabled India within the past decade, especially in last 5 years to develop proactive data collecting mechanisms and use them to shape better future.

In the preface, Okun’s law sheds light on the different aspects that Indian economy is undergoing as part of its growth process:

- Shift towards services’ and business sector

- Inflection within manufacturing sector

- Circulating workers that often swap between employment and unemployment;

Apart from the inflection within manufacturing sector, India is currently deploying all possible means to attract foreign as well as local businesses to setup operations here. Some of the finest examples being upcoming refinery project with ARAMACO in Maharashtra, organics ADANI-BASF in Gujarat and technology, Xiaomi in three other states.

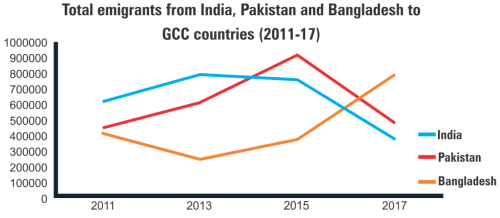

Source: Neha Wadhwaney, India Labour Migration Update 2018, ILO Country Office, New Delhi, Accessed on 26th Jan’2019

In context of partnering growth, Indian migrant labour market has dipped and Bangladesh has overtaken India in the last 4 years for GCC countries (ILO defined, now known as the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf). Overseas economic conditions especially within the GCC region have also changes, with more transparency and better access to employment derived rights, and yet, the migrant labour has chosen to stay put.

The turbulence from macroeconomic standpoint and as an ‘aspirational vortex’ within the employment sector can be summarized as follows:

- Lack of formal education or similarly applied level of attained education.

- Stringent application of above criteria, esp. for formal economy jobs.

- Limited and unreliable opportunities – for skill upgrade, or upskilling; learning relevant skills, or re-skilling and in today’s technology driven job market, reinventing personal skills, or neo-skilling.

- Compounding effects due to feedback loop of lack of skills – job demands and cascading loss of motivation.

- Loss of relevance and hence the personal identity of a ‘worker’ due to rising pressure

While a list of several more points can be identified and tabulated, the simple reason for the collective shortcomings can be traced to the informal sector – the 92% of us. While on one hand, the proposed unification of existing labour laws into 4 labour codes will stabilize the policy and overall decision-making framework; the questions related to ‘relevance’ within changing job scenarios and its rendezvous with ‘skill association’, remains to be answered.