How can perception of accidents with negative bias lead to a safety paradox?

When was the last time you read in the news something encouraging about health and safety? Something that does not define your perceptions for accidents? They are extremely rare and greatly outnumbered by unfavourable headlines. It’s possible to understand this propensity for scary stories.

But do our perspectives or behaviours alter because of what we just saw?

Or does the fact that we are not involved in similar circumstances only serve to soothe us as we sit in the safety of our own workplaces or homes? Alternatively referred to as the “that would never happen to me” syndrome.

Going from one extreme to the next

By following this line of thought, we’ll see that there are similarities to workplace health & safety. We frequently fall into the temptation of suggesting HSE defences to keep things under control.

Many of these “defence measures” reduce risks just slightly while costing the company a lot of money. Is this justified when there is so little chance that anything bad will happen?

Once these overzealous measures are put in place, we walk away thinking the job is done. While also feeling pleased that our ideas have been appropriately covered as a group. From this point on, everyone is content with a little dusting of paperwork and a splash of blissful ignorance.

This method harms the profession of health, safety, and the environment. Additionally, it jeopardises the existence of a behaviourally positive culture. From here, it is a quick descent towards complacency.

HSE Prosecutions continue to attract more clicks than anything else. Perhaps “negativity bias” contributes to the explanation of both the occurrence and the reasons why HSE has a reputation issue.

Instead of focusing on what we are doing well, we frequently choose to point out where others are making mistakes.

We have produced a bureaucratic monster by trying to defend ourselves by citing instances of when others have been harmed and then utilising maximum coverage.

This strategy will almost likely not advance health, safety, and environmental management in the long run. It contributes to the industry myths that the media actively promotes.

As a result, people lose interest in and connection with the goal of effective HSE management.

Do we inwardly adore tragedy?

Whether it was the Grenfell Fire, Hurricane Katrina, Fukushima, September 11th, or the earthquake in Haiti.

The incidents’ pictures were accidentally found online in a news article some time ago, and the circumstances look heartbreakingly terrible.

How did we come across such horrifying pictures? Such photographs seem to be appearing in an alarming number of media outlets.

It sometimes seems to be avoided, whether we consider an acid attack or a losing leg because of a crocodile bite.

Typically, pages have chosen to click on the tagline. As our emotional sensitivity to such material decreases, so does our immune to it.

Let’s delve a little more into the motivations behind viewing such visuals and how they affect the development of a safety paradox at work.

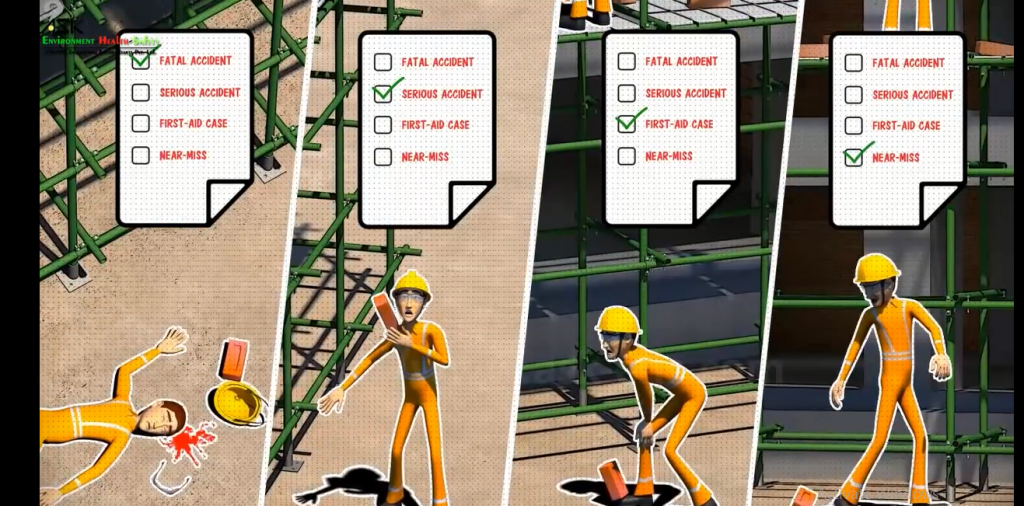

And here’s a small analysis of work at heights that presents an unbiased way of dealing with them –

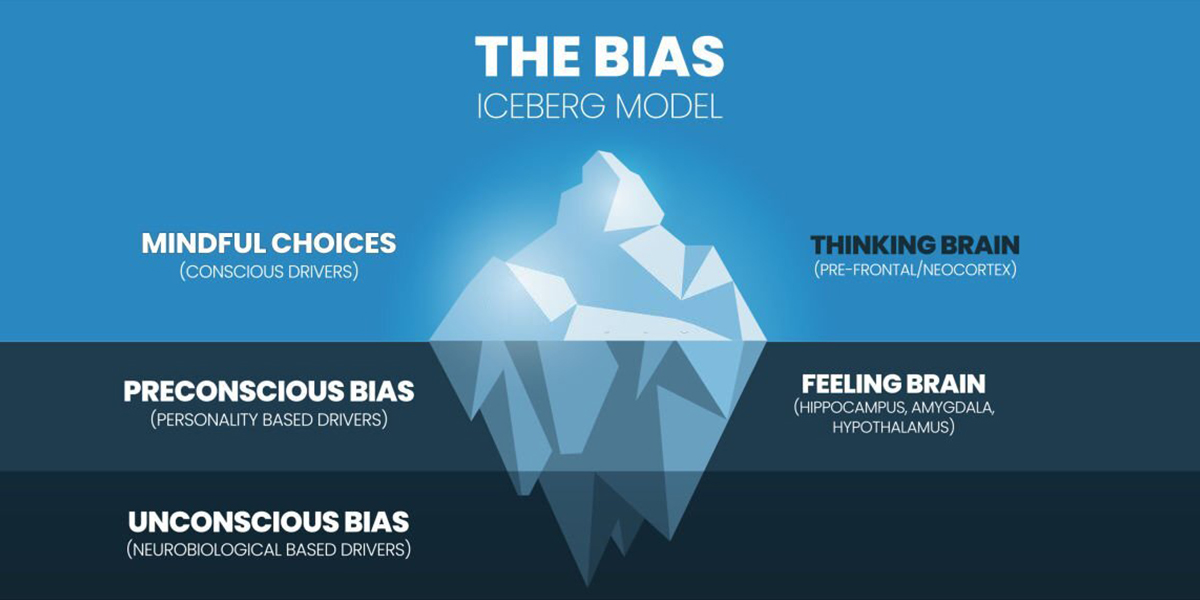

Unconscious bias toward the negative

Naturally, pictures wouldn’t be released if they weren’t working as clickbait and getting amazing viewing numbers. This could be because humans have a built-in “negativity bias.” Simply said, this is a survival instinct that aids in recognising and avoiding danger.

Believe it or not, as a primitive defence mechanism, we are unconsciously drawn to negative news.

One way to understand this paradox of disaster by relying on the idea that we will experience emotions is by refusing the assumption that was created when we initially presented this problem.

Namely that these negative emotions we think of in reaction to fiction are inevitably awful states.

This pessimism bias is mainly related to this tendency to overestimate how terrible the time can be for you, in the meaning that you overestimate the probability of bad consequences and underestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes.

In his study “Risk-Awareness as a Cultural Approach to Safety,” D. Borys identified a serious gap between management and employees. For very different reasons, both sides believed they were safe. By completing the necessary documents, management approved their function.

There are some examples of how this will change things, including the following. As much, the negative attitude is associated with several topics, including the increased prevalence of health problems and a difficulty in adjusting to new situations. Moreover, there is sometimes the common social stigma against despair, which may cause negative people to feel rejected by others.

As Burns defines it, psychological filtering is “pull out the bad point at any place and dwell on it entirely, so perceiving that the entire place is negative.” Leahy, Holland, and McGinn refer to this as “negative filtering,” which they determine as “focusing almost entirely on the negatives and rarely notice the positives.”

How can the Script be changed?

A methodical approach towards accidents and their happenings can help individuals direct their efforts towards finding the causes without any bias.

Learning methods such as eLearning and their courses help – devoting more time to truly adding value by utilising the advice and experience of others.

The majority of those who are impacted by workplace HSE have an opinion about it; in fact, many have steadfast beliefs and find it difficult to accept opposing viewpoints. If we want to fully utilize the human aspect of safety, we still need to have a mindset shift.

We might be able to show that we are in touch with what is occurring more effectively if we reduce the amount of paperwork and put less emphasis on measurements.

That guarantees that they can perform their duties with little chance of getting hurt.